Is America Headed for Another Civil War?

A recent Washington Post headline says: “In America, talk turns to something not spoken of for 150 years: Civil war.” The story references, among others, Stanford University historian Victor Davis Hanson, who asked in a National Review essay last summer: “How, when, and why has the United States now arrived at the brink of a veritable civil war?” Another Washington Post story reports how Iowa Republican Congressman Steve King recently posted a meme warning that red states have “8 trillion bullets” in the event of a civil war.

And a poll conducted last June by Rasmussen Reports found that 31 percent of probable US voters surveyed believe “it’s likely that the United States will experience a second civil war sometime in the next five years.”Is that legitimately where we stand today in the era of Donald Trump, particularly in the wake of the ramped-up rhetoric stemming from Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report on Russia’s interference in the 2016 election and whether the Trump campaign coordinated with Moscow, or is Civil War talk just crazy hyperbole? BU Today put three questions to Nina Silber, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of history and American studies and the current president of the Society of Civil War Historians.

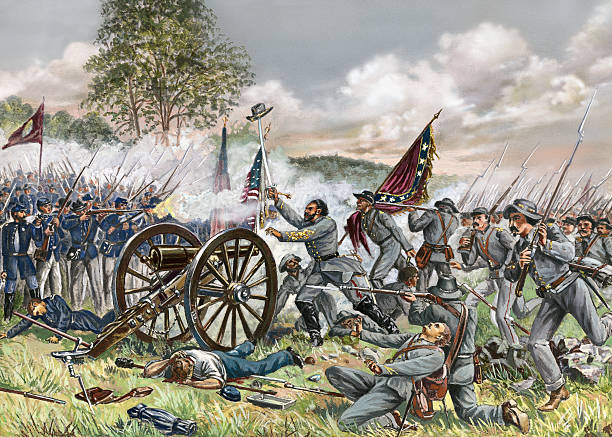

Silber has done extensive research on the Civil War over more than two decades and has written several books on the subject, including Divided Houses: Gender and the Civil War (1992), Daughters of the Union: Northern Women Fight the Civil War (2005), and most recently, This War Ain’t Over: Fighting the Civil War in New Deal America (University of North Carolina Press, 2018). Along with her teaching and research, she has worked on numerous public history projects, including museum exhibitions at the Gettysburg National Military Park and film projects on the Civil War and Reconstruction eras.So if anyone would have a knowledgeable perspective on the question of whether we are headed for civil war, it’s Silber. Read her answers about the proliferation of headlines referencing the possibility of another civil war.

BU Today: Democrats are demanding documents from President Trump, his family, and many associated with him. The political divide seems to be getting worse. Is it irrational to say this could be the beginning of a civil war?

Silber: I wouldn’t identify this most recent development [the demanding of documents] as the “beginning of a civil war” since I’m not sure that reflects anything other than the political divide we’ve already witnessed for the last several years and the fact that Democrats are taking steps they could not have taken before they regained control of the House. More ominous, I think, are indications of political violence and the willingness to enact political violence. This could be seen, for example, in the synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh, when the shooter spoke explicitly about targeting Jews who expressed sympathy for immigrants, or the recent case of the Coast Guard officer who was making plans to kill Democrats and journalists. I can imagine a future in which we deal with even more incidents of, or plans for, political violence—and that’s definitely a disturbing development. I’m troubled, too, by the role the president plays in contributing to this atmosphere.But it would have to be something else to call this a “civil war.” That would indicate a willingness on the part of masses of people to engage in violence against their political enemies. That happened in the 1860s, in part because people had come to see their political opponents in extreme, even demonic, ways and found it impossible to find any middle ground. Maybe our politics and culture are moving in that direction, but I don’t see it yet.

The political map these days shows so much red in the middle, sandwiched by blue on the coasts. How is that different from the North vs South divide of the Civil War?

The electoral map, at least from the most recent presidential election, does show blue coasts and a red middle. But I think that’s also a deceptive picture since we know that in many states, such as Florida, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan, there are deep internal divisions. In other words, it’s not the case that Florida, Pennsylvania, and others are overwhelmingly Republican. The same could be said for a number of “blue” states too. The geographic divide today is less clear-cut, less along solidly sectional lines.In 1860, the presidential contest reflected the way the political parties had divided and had become completely sectionalized. Many Southerners could not even vote for the Republican Party (which proclaimed opposition to the expansion of slavery) and the Democratic Party ran one candidate in Northern states (Stephen Douglas) and a different candidate in Southern states (John Breckinridge). Fundamentally, the split in the Democratic Party was over slavery: Southern Democrats were calling for a federal slave code (to regulate and permit slavery everywhere in the country) and Northern Democrats opposed this. As a result, the political divide reflected the division in the country between states that permitted slavery and states where it had been outlawed.

Some historians have been saying there was a similar political divide in 1860 to what we’re seeing today. Do you agree?

There may be a few historians who think the divide is similar, but I think most would say we’re looking at different patterns in our political divisions, although the tendency toward heated and extreme political rhetoric might be similar. The inability to find a political middle ground, certainly in the federal government, seems also to be similar.

Please support our work directly...